From last weekend when I was felled by a big bad bug:

As I am shut in this weekend trying to kick a respiratory bug, I've gotten hooked on YouTube.com. The past 24 hours I've been looking at performances and videos by

Corinne Bailey Rae, the British soul sensation whom one program touted as the second coming of

Billie Holiday and compared to

Lauryn Hill.

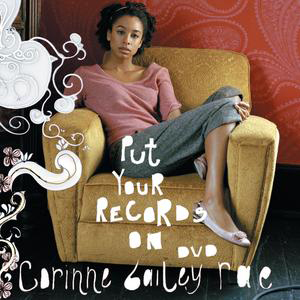

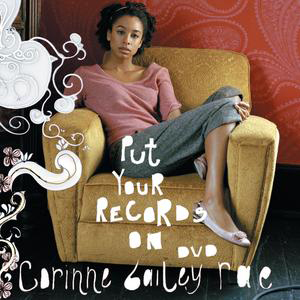

Corinne Bailey Rae is twenty-six years old, was born in Leeds to a mother who was a domestic worker, and recently hit the charts in the US with the single "Put Your Records On" and the latest hit "Like A Star" after signing a lucrative deal with EMI. Like a lot of folks I first heard of her when iTunes offered the acoustic version of that single from her eponymous debut, as their free single of the week. While I'll download some of the free singles I don't actually keep all of them or listen to them with any frequency but this song was an exception. More people have heard of her since her

October 7, 2006 appearance on Saturday Night Live.

OK, but the reason why I was moved to write about Bailey Rae is some of the hype she's received. One British entertainment show on BBC2, actually named "

The Culture Show", did

a profile of Bailey Rae that attempted a map of instigating factors for classic soul singers, creating analogies along the way to Bailey Rae. To wit: Bailey Rae like

Aretha Franklin and

Marvin Gaye grew up in the church, as Bailey Rae says "it was really important because it made me feel that music is a spiritual thing, and also that music kind of goes beyond words. My favorite parts on some of the record I've written are the wordless part...something that relates to the gospel singers--this wordless cry that came out of the church." The reportor continues, Franklin's and

Anita Baker's families were "close-knit, but hard up" and then draws a parallel to Bailey Rae's upbringing where sometimes they had a "car" a "phone" or a "tv" but not on a regular basis. She doesn't see it as a defining factor, but that not being able to afford to go out to the cinema and other things meant that her family used their imagination a lot, writing songs and making up plays.

Interestingly the profile begins with the assertion that Bailey Rae had been compared to "branded" artists such as "

Norah Jones and

Joss Stone" but that Bailey Rae had a "pedigree" similar to soul singers of an earlier era. Fascinating wording. Well the British music hype machine is reknowned for its levels of enthusiasm that then invert and eat their own. But here the part that intrigues me is the notion that there is a "pedigree" of spirituality and poverty that makes one a "true soul singer"--thus disincluding Jones and Stone--and that is implicitly paired with race--again disincluding Jones and Stone--to create something "natural" and "authentic". They continue with the notion of "struggle": a soul artist has to pay their dues, pointing to the examples of Anita Baker giving up her dream for a time after being told she couldn't sing, and Luther Vandross' having spent 20 years writing jingles (they neatly sidestep all his years of honing his skills writing songs for other artists and the theater, and singing backup for David Bowie, Chaka Khan, Barbara Streisand, etc. and earning 600k per year writing and singing those jingles--the brother knew how to work a hook and a stage show). Bailey Rae isn't a packaged commodity, having worked as a musician since she was 18. "But does she have the goods"? "The Culture Show" hosts ask in the final minutes of the segment and then cut to Bailey Rae singing live with spare acoustic accompaniment.

What is true about Bailey Rae is that she is skilled at accessing an emotional wellspring with her voice. At this point I've seen multiple performances of "Like a Star" and "Put Your Records On" and although each is quite similar, down to her facial expressions, each is also deeply nuanced and has an energy that is fresh and new. Maybe it's the thrill of touring for the first time, but each clip of her singing each of the above singles features her face spilling over with joy (it's contagious), looking like there's no place she'd rather be, and nothing she'd rather be doing. If you could separate the emotional

quality out from her actual voice I'm not sure I could pick Bailey Rae out of a crowd. However, its presence makes me want to listen to her sing repeatedly, and will likely result in me anteing up cash for an album full of love songs, which I typically don't do; even though the album doesn't contain one of my favorite cuts by

her:

"Since I've Been Loving You". This lyrically repetitive bluesy number is a great showcase for Bailey Rae's way with the wordless sound, the bent note, and her highly available emotional presence as a performer. Plus she's got a really great backing band, they are tight, and this live performance features some really solid front of house (FOH) mixing, well it is a BBC session--land of the premier audio broadcast engineers.

The pairing of poverty, struggle, and soul (read "black authenticity") has always bothered me. That kind of authentication seems a mighty convenient way to marry black birthright to economic and educational disenfranchisement since the latter two usually go hand in hand. Add to that the valorization of that crucible of causation via the paydirt of critical and popular success and you've got a convenient legacy of ambivalence towards second and third generation economically solvent and successful black folks trying to do anything creative or employ any creative tools to talk about being black. I'm probably thinking about this more than usual because I am simultaneously reading scholar

William T. Dargan's

Lining Out the Word: Dr. Watts Hymn Singing in the Music of Black Americans,

poet and Cave Canem co-founder Toi Derricotte's often unsparingly honest The Black Notebooks and Daphne A. Brook's study which takes the interdisciplinarity in Performance Studies to a whole new level in Bodies in Dissent: Spectacular Performances of Race and Freedom 1850-1910. The first of these deals with the hymn-lining tradition in many black Baptist churches, particularly Missionary Baptist, beginning during slavery and and continuing through the 1970s. Dargan spends some time detail how hymn-lining was more acceptable to the plantation owners and overseers than ring shouts because the slaves sang in English and they sang Christian hymns that taught that religious doctrine simultaneous with justifying slavery. Me, I think all those wordless gestures and cries are where the subversive messages were, and an important part of the strength and resilience that was gained from the hymn-lining tradition, during times of subservience and subversion. An enslaved woman might not be able to intone the words, "you killed my boy and raped first my daughter and then me" at a slave service but she surely could wordlessly moan about it within the hymn-lining tradition, or bend a note the way that Mahalia Jackson, who studied the hymn-lining tradition, does at the end of her 1950s era rendition of Thomas A. Dorsey's "Precious Lord" when she sings "home" so that two notes are simultaneously audible, signifying a complex notion of what constitutes "home". Brooks looks at the performance of gender particular in the trans-racial and transgender performances of Adah Isaacs Menken which allowed the stage star to both keep folks guessing about who and what she really was in turn allowing her a certain freedom from the constraints of any given identity--as long as she was "performing" ('can't stop dancing, you can never stop dancing') which is something that black women, and men for that matter, face all the time: various permutations of wearing the mask, being masked and negotiating when and where to let it slip down past the vulnernable heart. But my interest is not just the performance outward to an audience of a certain power and status, I am also thinking about the performance inward and within the community of identification, this prismatic or triangulated approach is what struck me about The Black Notebooks which is probably the most relentlessly naked account of a black woman's experience of internalized racism and being the subject of externally projected racial prejudice that I've ever read. As I think about the middle-class identified Derricotte's writing, I hear the echoes of "not for the faint of heart," and "this is not your daddy's horror story" (except that in some ways it surely is), which is to say it reminded me, in

looks at the performance of gender particular in the trans-racial and transgender performances of Adah Isaacs Menken which allowed the stage star to both keep folks guessing about who and what she really was in turn allowing her a certain freedom from the constraints of any given identity--as long as she was "performing" ('can't stop dancing, you can never stop dancing') which is something that black women, and men for that matter, face all the time: various permutations of wearing the mask, being masked and negotiating when and where to let it slip down past the vulnernable heart. But my interest is not just the performance outward to an audience of a certain power and status, I am also thinking about the performance inward and within the community of identification, this prismatic or triangulated approach is what struck me about The Black Notebooks which is probably the most relentlessly naked account of a black woman's experience of internalized racism and being the subject of externally projected racial prejudice that I've ever read. As I think about the middle-class identified Derricotte's writing, I hear the echoes of "not for the faint of heart," and "this is not your daddy's horror story" (except that in some ways it surely is), which is to say it reminded me, in its most wrenchingly honest parts, of being in a theater watching a truly suspenseful and emotionally harrowing horror movie, except it was real life, sometimes just plain old everyday life. At least at the end of a horror movie I am comforted (eventually) by the reality there are no monsters lurking around the corner or under the bed. What struck me though about all the blurbs of praise on the back of the book is that on the surface they celebrate the content of the work, how it is an important book about race and racism. What is easy to miss is how each of these writers are also acknowledging the praise-worthy skill of Derricotte's writing. Reading the passages I was continuously aware of the twenty years of writing, and many revisions, from which this short tome has emerged. Toi Derricotte ain't no joke.

its most wrenchingly honest parts, of being in a theater watching a truly suspenseful and emotionally harrowing horror movie, except it was real life, sometimes just plain old everyday life. At least at the end of a horror movie I am comforted (eventually) by the reality there are no monsters lurking around the corner or under the bed. What struck me though about all the blurbs of praise on the back of the book is that on the surface they celebrate the content of the work, how it is an important book about race and racism. What is easy to miss is how each of these writers are also acknowledging the praise-worthy skill of Derricotte's writing. Reading the passages I was continuously aware of the twenty years of writing, and many revisions, from which this short tome has emerged. Toi Derricotte ain't no joke.

All of which is to say, BBC2, that's a lot of hype to lay on a 26 year-old black female artist with a single album to her credit, who is heir to any number of legacies about African American and African diasporic women soul music artists. I just hope Bailey Rae will continue to enjoy herself, and do her own thing.

All of which is to say, BBC2, that's a lot of hype to lay on a 26 year-old black female artist with a single album to her credit, who is heir to any number of legacies about African American and African diasporic women soul music artists. I just hope Bailey Rae will continue to enjoy herself, and do her own thing.

poet/performer/percussionist Karma Mayet Johnson (pictured left) at the Cave Canem 10th Anniversary Celebration, in which Johnson had written of the relationship between two female slaves who were separated when the plantation master who had been regularly raping one of them finds the two of them in an intimate moment together. After unsuccessfully attempting to beat both of them to death, he sells one of the women to another plantation. The woman who is sold grieves the loss of her lover, until another woman opens up her heart to her, while the woman who is left behind holds the memory of her lover and the love they shared close to her by tending to the indigo plants her lover left behind. The indigo that her lover plants by the river becomes her own nurturance, the love of which she shared with her lover and became a thing that grew and wove them together, affirming their lives as more than property of the slaveholder. By the end of Johnson's reading there were tears throughout the room, at the pain these women endured, but also the profundity of love, of the spirit to insist on and pursue the capacity to feel something beautiful in one's heart and under one's fingertips.

poet/performer/percussionist Karma Mayet Johnson (pictured left) at the Cave Canem 10th Anniversary Celebration, in which Johnson had written of the relationship between two female slaves who were separated when the plantation master who had been regularly raping one of them finds the two of them in an intimate moment together. After unsuccessfully attempting to beat both of them to death, he sells one of the women to another plantation. The woman who is sold grieves the loss of her lover, until another woman opens up her heart to her, while the woman who is left behind holds the memory of her lover and the love they shared close to her by tending to the indigo plants her lover left behind. The indigo that her lover plants by the river becomes her own nurturance, the love of which she shared with her lover and became a thing that grew and wove them together, affirming their lives as more than property of the slaveholder. By the end of Johnson's reading there were tears throughout the room, at the pain these women endured, but also the profundity of love, of the spirit to insist on and pursue the capacity to feel something beautiful in one's heart and under one's fingertips.