James Brown Symposium at Princeton University November 29-30: Part I

If Elvis Presley/is

King

Who is James Brown,

God?

-Amiri Baraka "In the Funk World"

This event was surely a roll call moment--you wouldn't have wanted to not be there if you could--which accounted for hip hop living legend Chuck D and legendary radio personality, hip hop historian, and KMEL program director Davey D flying in from California to catch the Friday afternoon sessions.

Many of the comments as people looked around were about how their idols were present the aforementioned Chuck D and Davey D, music journalists Greg Tate, Robert Christgau and Kandia Crazy Horse; the "number 1 funky public intellectual" Cornel West; Center for African American Studies Director and brilliant scholar, Valerie Smith; scholars Farah Jasmine Griffin (whose book on Billie Holiday has my all-time favorite title--If You Can't Be Free, Be A Mystery)

Of course the major stars on the scene were the people who lived the story the Symposium had undertaken to explore, former James Brown band members and musical directors Fred Wesley and Pee Wee Ellis, and former James Brown Revue Tour/Road Manager Alan Leeds. Wesley has written a fantastic book about his experiences, Hit Me Fred: Recollections of a Sideman, which was published by Duke University Press in 2002 and is available in paperback.

DAY 1

The event started with an introduction by Center for African American Studies Director Valerie Smith. You can't go wrong with a Valerie Smith introduction, and she of course acknowledged her former mentee, and now colleague, the also singularly accomplished Daphne A. Brooks. This post might be sounding rather hyperbolic. Too bad. It was just one of those events where brilliance was the baseline functionality of the majority of the folks that hit the stage. If you were there you saw manifest the acumen that had put together the line-up. It was no small feat getting all these people together, and coming up with the right alchemy of voices on each panel to make the whole event really sing. So hats off to Daphne A. Brooks for organizing and realizing the vision of this event. Those who weren't in attendance were sorely missed by all, and yet what was presented there was rich and thought-provoking.

Brooks introduced Alan Leeds and Harry Weinger, Vice President of A&R for Universal Music Enterprises and a surprisingly down-to-earth guy (very sweet to see his rapport with his teenage son later on during a break between panels). Universal Music Enterprises is the "catalog reissue arm of Universal Music Group." So Weinger is the guy who gets to go into the vaults and check out old masters and produce a number of catalog reissues, including much James Brown and Motown work. He also co-produced the celebrated James Brown Star Time 4-CD Box Set (an oft repeated comment during the symposium was "Harry has the best job ever!" To which he responded in agreement with outstretched arms and a big smile).

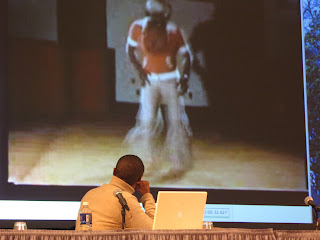

Leeds and Weinger had taken on the task of selecting vetting through tapes of James Brown concert footage to find footage that would best represent the complexity of James Brown the performer, band leader, and man. The chose footage from a 1968 concert which I believe occurred three weeks before the famous Boston concert that took place the day of Martin Luther King's assassination and was broadcast live and then aired throughout the night and kept people from taking their anguish onto the streets in undirected energy that often can become misdirected into the destruction of one's own community and city. So that was the day James Brown saved Boston. The footage Leeds and Weinger shared was without the conscious onus of keeping peace in a city long known for racial strife. The video showed an edited concert from the Apollo Theatre for television broadcast, James Brown: Man to Man. The original concert was about 90 minutes but the tape was 45. We were lucky that it showed him at the height of some of his dance moves and choreography even though it kept cutting away to

silkscreen graphic images of Brown (the original editor was definitely not thinking like an archivist). Apparently, there is a lot of James Brown footage out there, but legal red tape has prevented it from being made available to the public. There is some hope that this will change in the near future. I had never seen James Brown live. By the time I was of an age to choose to go to a James Brown concert the heyday of the J.B.'s was over, and as some of the speakers acknowledged, Brown had become a caricature of himself. The footage gave a sampling of Brown's "lounge act" crooning, his high energy performance numbers, and the famous cape sequence with not one, but three increasingly ornate individual sequined capes

silkscreen graphic images of Brown (the original editor was definitely not thinking like an archivist). Apparently, there is a lot of James Brown footage out there, but legal red tape has prevented it from being made available to the public. There is some hope that this will change in the near future. I had never seen James Brown live. By the time I was of an age to choose to go to a James Brown concert the heyday of the J.B.'s was over, and as some of the speakers acknowledged, Brown had become a caricature of himself. The footage gave a sampling of Brown's "lounge act" crooning, his high energy performance numbers, and the famous cape sequence with not one, but three increasingly ornate individual sequined capes The subsequent keynote panel included music critic Robert Christgau, scholar Farah Jasmine Griffin, the previously mentioned Alan Leeds, and scholar Fred Moten (late of University of Southern California and on his way, this January, to North Carolina to join fellow presenter Mark Anthony Neal at Duke University)(see above right, Moten, Christgau, Griffin, Leeds, and Brooks). Moten cited the footage of Brown walking through decimated parts of Harlem, and Washington, D.C. talking about his concept of people razing these buildings and having people reconstruct their neighborhoods--not flee them but redesign them. Moten wove a poignant portrait of these blighted areas as areas from which people fled, their success as African Americans determined by their ability to leave these areas and yet their sense of identity is caught up in those locations. One of the discussions that occurred was the contradictory nature of the rent party--figured in a lyric within a Brown song. Highlighted is the fact that one is living under duress, vulnerable to police harassment, but it is one's home and funds are to pay the rent so that you have a home. At the same time desire is to flee, while taking part in the rituals of home culture, the place from which one simultaneously wants distance and lived memory. Christgau, gave both mea culpa for and revised history of the profound lack of understanding for James Brown's genius during the heyday of his innovations quoting writing from both white and African American critiques which complained of the ways in which Brown was moving beyond currently popular R&B paradigms without recognizing what those revolutionary moves would mean for future musics. Griffin (above left listening to Leeds), spoke

The subsequent keynote panel included music critic Robert Christgau, scholar Farah Jasmine Griffin, the previously mentioned Alan Leeds, and scholar Fred Moten (late of University of Southern California and on his way, this January, to North Carolina to join fellow presenter Mark Anthony Neal at Duke University)(see above right, Moten, Christgau, Griffin, Leeds, and Brooks). Moten cited the footage of Brown walking through decimated parts of Harlem, and Washington, D.C. talking about his concept of people razing these buildings and having people reconstruct their neighborhoods--not flee them but redesign them. Moten wove a poignant portrait of these blighted areas as areas from which people fled, their success as African Americans determined by their ability to leave these areas and yet their sense of identity is caught up in those locations. One of the discussions that occurred was the contradictory nature of the rent party--figured in a lyric within a Brown song. Highlighted is the fact that one is living under duress, vulnerable to police harassment, but it is one's home and funds are to pay the rent so that you have a home. At the same time desire is to flee, while taking part in the rituals of home culture, the place from which one simultaneously wants distance and lived memory. Christgau, gave both mea culpa for and revised history of the profound lack of understanding for James Brown's genius during the heyday of his innovations quoting writing from both white and African American critiques which complained of the ways in which Brown was moving beyond currently popular R&B paradigms without recognizing what those revolutionary moves would mean for future musics. Griffin (above left listening to Leeds), spoke  about the complex relationship her female elders had to James Brown as he moved through his various aesthetic, political and sexual politic phases--the conk about which one aunt was heard to say "only one of us can wear rollers to bed and it can't be my husband"; Brown's insistence that "It's a Man's World"; Brown's support of presidential candidate Richard M. Nixon; Brown's domestic battery arrests about which the aunts commented, "I guess he really did believe it was a man's world"; the increasing employ of white backup singers in his revue in his latter years as a performer; and his performance of the controversial "Living in America" in Rocky IV (1985) and on the film's soundtrack. But through all that the aunts never abandoned Brown, he still had a place on their turntables, tape, and CD players. Alan Leeds commented on Griffin's talk noting that during his latter years Brown became something of a caricature of himself, and likely performed "Living In America," which he didn't write, in order to get back into the public eye. A goal at which he succeeded. (above left, Moten and Christgau share a moment; below right, Jason King contemplates James Brown as dance teacher

about the complex relationship her female elders had to James Brown as he moved through his various aesthetic, political and sexual politic phases--the conk about which one aunt was heard to say "only one of us can wear rollers to bed and it can't be my husband"; Brown's insistence that "It's a Man's World"; Brown's support of presidential candidate Richard M. Nixon; Brown's domestic battery arrests about which the aunts commented, "I guess he really did believe it was a man's world"; the increasing employ of white backup singers in his revue in his latter years as a performer; and his performance of the controversial "Living in America" in Rocky IV (1985) and on the film's soundtrack. But through all that the aunts never abandoned Brown, he still had a place on their turntables, tape, and CD players. Alan Leeds commented on Griffin's talk noting that during his latter years Brown became something of a caricature of himself, and likely performed "Living In America," which he didn't write, in order to get back into the public eye. A goal at which he succeeded. (above left, Moten and Christgau share a moment; below right, Jason King contemplates James Brown as dance teacher during Thomas F. DeFrantz's presentation)

during Thomas F. DeFrantz's presentation)

DAY 2

I unfortunately missed the talks by both Mark Anthony Neal and Jason King which were roundly lauded by everyone with whom I spoke, and they added a "mmph, you shoulda been there!" raised eyebrow for good measure. Oh well. I did get to see and hear almost the entirety of dance scholar Thomas F. DeFrantz's intriguing presentation, "My Brother, the Dance Master" (left) which was followed up by UCLA musicologist Robert Fink's boisterous and rhythm driven consideration of Brown's 1971 linguistic and philosophical summation, "Soul Power." Fink traced both Brown's strategy in getting African diasporic and multi-cultural audiences to take up the philosophy of Soul Power and how it operated as a response to the more exclusive "Black Power" shout out which then Stokely Carmichael and another black Freedom Summer worker had, working a strategy similar to a grassroots call-and-response campaign, supplanted the established "What do we want?" "Freedom Now!" call-and-response exchange with "What do we want?" "Black Power!" (below right, Robert Fink shows his graphical representation of the distinct rhythmic emphases in the call-and-response oral/aural compositions "Black Power" and "Soul Power")

(right, Neal answering a question while King and DeFrantz look on below the reprint of the US Constitution and liner note included in Brown's 1971 release Revolution of the Mind)

The early afternoon panel featured rock critic (Rip It Up: The Black Experience in Rock & Roll) Kandia Crazy Horse's ode to "King James" and his musical

and social revolutionary acts, during which she repeatedly queried "who is next? Who is in place to take up the mantle of Brown?"(above left) Interestingly Jason King had earlier suggested it might be Sharon Jones who just released a double CD with The Dap-Kings(right), 100 Days 100 Nights. Funk historian and radio DJ Rickey Vincent's "James Brown and the Rhythm Revolution" detailed the historical connections between Brown's rhythmic progressions and the rhythms of hip hop. He

and social revolutionary acts, during which she repeatedly queried "who is next? Who is in place to take up the mantle of Brown?"(above left) Interestingly Jason King had earlier suggested it might be Sharon Jones who just released a double CD with The Dap-Kings(right), 100 Days 100 Nights. Funk historian and radio DJ Rickey Vincent's "James Brown and the Rhythm Revolution" detailed the historical connections between Brown's rhythmic progressions and the rhythms of hip hop. He  spoke of having repeated discussions with a hip hop culture writer about the importance of Brown's work to the formation of hip hop beats and how this was consistently met with deflection until one day someone gave this friend the Star Time collection. It sat on his dashboard until one day he sheepishly greeted Vincent with, "Man, man, why didn't you tell me, I totally get it, now." The Roots' Questlove had a conversation with Princeton history professor (and sometime DJ) Joshua B. Guild about how he came to the work of James Brown, and how he sees Brown's legacy operating in current hip hop musical formations. Above left, Harry Weinger who dedicated his talk to the late Tom Terrell, flanked by Crazy Horse and Vincent as he related the work of putting together the Grammy award-winning Star Time boxed set and "Listening to James Brown."

spoke of having repeated discussions with a hip hop culture writer about the importance of Brown's work to the formation of hip hop beats and how this was consistently met with deflection until one day someone gave this friend the Star Time collection. It sat on his dashboard until one day he sheepishly greeted Vincent with, "Man, man, why didn't you tell me, I totally get it, now." The Roots' Questlove had a conversation with Princeton history professor (and sometime DJ) Joshua B. Guild about how he came to the work of James Brown, and how he sees Brown's legacy operating in current hip hop musical formations. Above left, Harry Weinger who dedicated his talk to the late Tom Terrell, flanked by Crazy Horse and Vincent as he related the work of putting together the Grammy award-winning Star Time boxed set and "Listening to James Brown." The final panel of the afternoon, began with culture journalist Ernest Hardy (Blood Beats, Vol. I and the forthcoming Blood Beats, Vol. II) and his read of the implicit homophobia present in Brown's lyrics and stance, and his initial alienation from Brown's work, and alternately how he found a way in which the aspects of Brown's language and performance gestures outlined a certain ambiguity and vulnerability and thus particularly included him in its complex renderings and performances of masculinity.

The final panel of the afternoon, began with culture journalist Ernest Hardy (Blood Beats, Vol. I and the forthcoming Blood Beats, Vol. II) and his read of the implicit homophobia present in Brown's lyrics and stance, and his initial alienation from Brown's work, and alternately how he found a way in which the aspects of Brown's language and performance gestures outlined a certain ambiguity and vulnerability and thus particularly included him in its complex renderings and performances of masculinity.Legal scholar and English professor Imani Perry mined similar terrain as explored the previous day in Griffin's presentation, but was more pointed in talking about the problematic propensity of some black male genius toward the battering of their female partners--allowing

their fear, anxiety, and insecurity to turn into a physicalized rage and enacting that on someone close to (emotionally and physically) themselves whom they can dominate therefore shoring up their fragile sense of self (I was so focused on her eloquent frankness I forgot to take a photo!). Perry also made some important distinctions between misogyny and sexism. Noting that Brown didn't exactly approve of the use of his samples for hip hop beats because he felt much of the music degraded women. Seemingly at odds with someone who would sing "It's A Man's World" or "Payback" or assault his own wife. But at the same time Brown apparently could be supportive of the women around him. And Perry pointedly addressed the musical arrangement

their fear, anxiety, and insecurity to turn into a physicalized rage and enacting that on someone close to (emotionally and physically) themselves whom they can dominate therefore shoring up their fragile sense of self (I was so focused on her eloquent frankness I forgot to take a photo!). Perry also made some important distinctions between misogyny and sexism. Noting that Brown didn't exactly approve of the use of his samples for hip hop beats because he felt much of the music degraded women. Seemingly at odds with someone who would sing "It's A Man's World" or "Payback" or assault his own wife. But at the same time Brown apparently could be supportive of the women around him. And Perry pointedly addressed the musical arrangement  of "Man's World" as lament rather than swaggering declaration. Mendi Obadike (left, flanked by Imani Perry and Greg Tate) spoke about the "The Pleasure/Challenge of James Brown's Iconicity," specifically in relation to key iconic moments during Brown's funeral in Augusta, Georgia, including Vicki Anderson's singing of "It's A Man's World" after relating the story of Brown having written the song (with Betty Newsom) following a conversation with Anderson in which he commented that "it was a man's world" and Anderson countered with "yeah , but it wouldn't be anything with women." Reportedly Anderson sang the song raw, with her voice giving out.

of "Man's World" as lament rather than swaggering declaration. Mendi Obadike (left, flanked by Imani Perry and Greg Tate) spoke about the "The Pleasure/Challenge of James Brown's Iconicity," specifically in relation to key iconic moments during Brown's funeral in Augusta, Georgia, including Vicki Anderson's singing of "It's A Man's World" after relating the story of Brown having written the song (with Betty Newsom) following a conversation with Anderson in which he commented that "it was a man's world" and Anderson countered with "yeah , but it wouldn't be anything with women." Reportedly Anderson sang the song raw, with her voice giving out.Greg Tate closed out the panel with his read of "blues and the nekkid truth--the embodied she-funks of betty davis, chaka khan, grace jones and meshell ndegeocello." Tate related the degree to which Chaka Khan had control over her career, albums and

songwriting, and the way that Grace Jones functioned as both the media creation of her one-time husband/"svengali" photographer Jean-Paul Goude, and a highly conscious vocal stylist. He illustrated the controversial and larger-than-life presence of Betty Davis with stories from his friend's explosive memories of seeing Davis perform on the Howard University campus back in the day, her rawness, and relentless funk rhythms. He also illuminated the way MeShell Ndegeocello was received by her male colleagues with a choice story from Jared Nickerson, bassist with Tate's Burnt Sugar Arkestra, who commented that when male bassists saw MeShell Ndegeocello play they didn't say she could play well for a woman/girl, "they went home and practiced!" (Tate above right, flanked by Obadike and moderator Tavia N'yongo)

songwriting, and the way that Grace Jones functioned as both the media creation of her one-time husband/"svengali" photographer Jean-Paul Goude, and a highly conscious vocal stylist. He illustrated the controversial and larger-than-life presence of Betty Davis with stories from his friend's explosive memories of seeing Davis perform on the Howard University campus back in the day, her rawness, and relentless funk rhythms. He also illuminated the way MeShell Ndegeocello was received by her male colleagues with a choice story from Jared Nickerson, bassist with Tate's Burnt Sugar Arkestra, who commented that when male bassists saw MeShell Ndegeocello play they didn't say she could play well for a woman/girl, "they went home and practiced!" (Tate above right, flanked by Obadike and moderator Tavia N'yongo)

(left, the appreciative audience applauding the keynote panel and Daphne A. Brooks' efforts on Day 1--a number of folks came in late and were sitting on the sides of the Auditorium, so the turn out was more than what you see here; right, a fuller (and more centrally-seated, but still a lot of folks were on the side) house giving it up again for Brooks and James Brown on Day 2. Richardson Auditorium, Alexander Hall, Princeton University)

PART II: Coming Up...

Labels: Daphne A. Brooks, Farah Jasmine Griffin, Fred Moten, Fred Wesley, James Brown, Pee Wee Ellis, Questlove, Rickey Vincent

1 Comments:

As I wrote in my other note, you really pen a great account of this amazing event. I wish I could have been there!

Post a Comment

<< Home