Bit a this and that

The rape allegations againsts members of the Duke lacrosse team is old news at this point, but Mark Anthony Neal's Duke African American and American Studies blog has a great article from The Independent Weekly, a North Carolina Triangle area paper, dealing with a protest vigil held after the alleged crime was reported. African American Duke students at the protest talked about their experiences at the university and in racially mixed social situations where black women are often treated as receptacles for white male "video ho" desire. Apparently even study dates with previously respected white male classmates have been known to devolve into this dynamic.

A few weeks back Creative Loafing (Atlanta edition) finally did another cover story about MARTA the downtrodden public transportation system in Atlanta, updating their better researched cover story of two years ago. Atlanta, relative to the

size of the populace and level of urban development has one of the worst public transportation systems in the country. The city also has a deeply ingrained car culture--people look at you as though you are mentally ill if you chose not to drive. This attitude is not entirely without rationale. The failures of MARTA are magnified by the fact that Atlanta's development sprawl has moved outwards to the suburbs and it is one of the few major city transportation systems that receives no funding from either the city or the state.

size of the populace and level of urban development has one of the worst public transportation systems in the country. The city also has a deeply ingrained car culture--people look at you as though you are mentally ill if you chose not to drive. This attitude is not entirely without rationale. The failures of MARTA are magnified by the fact that Atlanta's development sprawl has moved outwards to the suburbs and it is one of the few major city transportation systems that receives no funding from either the city or the state. (Photo: Michael Wall; ON HOLD: Alexia Howard waits at a MARTA stop in front of her apartment complex in Decatur.)

'What is going on currently with the state and any potential funding of MARTA is rooted in 35 years of racism and classism,' says Terence Courtney, coordinator with Atlanta Jobs with Justice, a group of low-income, elderly and disabled riders who depend on MARTA. 'Those lawmakers did not contribute operation funds from the beginning, which limited MARTA's ability to expand and serve the community.'

It's true that state lawmakers don't give MARTA a dime for fuel, salaries or maintenance of its stations, buses and trains. Nor do they provide money for any of MARTA's day-to-day needs. Unlike lawmakers in every other state with a major transit system, they never have.

MARTA riders' fares only cover about a third of the cost of a ride. The rest of the trip is paid for by federal grants and the 1-cent sales tax levied by Fulton and DeKalb counties and the city of Atlanta. The tax and the $1.75 fare are the sole sources of operation funds for the transit agency. And those sources do not generate enough revenue to operate and maintain the region's oldest and most heavily used transit system.

Originally the transit system was meant to serve five counties, but the suburbanites in those outlying counties refused a $.01 sales tax increase. According to Robert Bullard, a professor at Clark Atlanta University, whose work focuses on transportation and labor, for a number of the predominantly white residents of those areas the name of the system stands for "Moving Africans Rapidly Through Atlanta," and it's a movement they'd rather curtail. And why not? According to the 2004 story that year the state Department of Transportation allocated $12 million to those suburbs for their own transportation system, for a combined ridership that doesn't equal that of MARTA while supposedly allocating $2 million to MARTA, which seems to never have been distributed to the ailing system. At the same time all the downtown Atlanta gentrification has reduced the amount of affordable housing in the heart of MARTA's service areas. So the "African" element is living closer to the suburbs anyway. Meanwhile the limited budget has resulted in major service cuts over the past two years with some bus lines cutting later evening and weekend service entirely. Sorry if you needed to work that Sunday shift, maybe you can catch a $35 cab ride across town. One would think that all those whites employing African American and Latina/o domestic and garden workers would want them to get to their jobs on time. But it seems the projected fear of what ease of access might lead to has negated that desire: burglary, possible homeownership--which naturally leads to miscegenation--all of which for some are a part of the same property devaluation coin). Back in the 1960s along with multiple county service the designers of MARTA aspired to create a system "on par with transit agencies in the nation's major cities, such as Boston, San Francisco and Seattle." Just to give you sense of how MARTA, which is comprised of rail and bus service, compares to the systems of other cities let's compare it to the rail maps of those other systems:

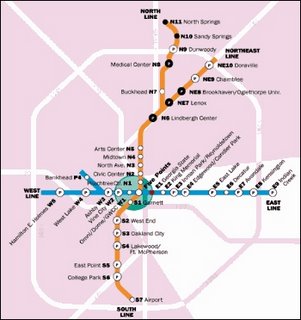

Atlanta's metro rail system (left, below; c. 2004:470,000 riders/day)

Atlanta's metro rail system (left, below; c. 2004:470,000 riders/day)

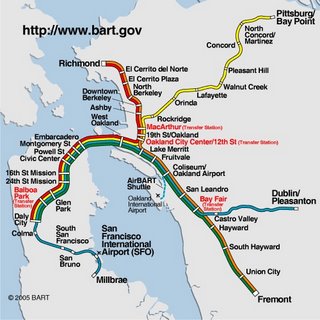

SFBay Area rail system (right, above; c.2004: 306,570 riders/weekday)

Boston's subway & commuter system (left below; c.2005:1.12 million riders/weekday) Washington D.C. metro (right, below; c.2004: 520,000 riders/day)

It just wouldn't have been fair to include the NYC subway system(3.9 million riders/day). But D.C. and Boston are good comparisons, although the greater-Atlanta area may have more in common with Oakland (which serves a smaller population than Atlanta) or Los Angeles in terms of the sprawl and ingrained car culture. In fact it was a recent post by blogger Anovelista that included a reference to public transporation user demographics in Los Angeles reminding me of their similarity. I'm used to systems that are fairly equalizing, where everybody rides the subway, rich, poor, whites, folks of color, old, young, disabled and (temporarily) able-bodied. So the class and race segregation and quality of service on MARTA is quite marked to me. Soon after having to deal with MARTA I took to sarcastically (Ok bitterly) calling it "the New Underground Railroad," and not in a good way: a . It's mainly transportation for the poor, and disabled, and a few commuters. The last primarily live on the suburban North-South line which has the newest cars that don't overwhelm with the odor of years-old mold, and aren't home to baby german roaches (e.g. the dark ones on the right). But in the main MARTA's customers are Blacks (African Americans, Africans, and Afro-Caribbeans), the poor, and disabled, and on certain parts of the system, Mexican and Central American immigrants. The exceptions are the white families riding on droves during major sporting events (those days are obvious), and the broad cross-section of people using MARTA to get to the airport.

It just wouldn't have been fair to include the NYC subway system(3.9 million riders/day). But D.C. and Boston are good comparisons, although the greater-Atlanta area may have more in common with Oakland (which serves a smaller population than Atlanta) or Los Angeles in terms of the sprawl and ingrained car culture. In fact it was a recent post by blogger Anovelista that included a reference to public transporation user demographics in Los Angeles reminding me of their similarity. I'm used to systems that are fairly equalizing, where everybody rides the subway, rich, poor, whites, folks of color, old, young, disabled and (temporarily) able-bodied. So the class and race segregation and quality of service on MARTA is quite marked to me. Soon after having to deal with MARTA I took to sarcastically (Ok bitterly) calling it "the New Underground Railroad," and not in a good way: a . It's mainly transportation for the poor, and disabled, and a few commuters. The last primarily live on the suburban North-South line which has the newest cars that don't overwhelm with the odor of years-old mold, and aren't home to baby german roaches (e.g. the dark ones on the right). But in the main MARTA's customers are Blacks (African Americans, Africans, and Afro-Caribbeans), the poor, and disabled, and on certain parts of the system, Mexican and Central American immigrants. The exceptions are the white families riding on droves during major sporting events (those days are obvious), and the broad cross-section of people using MARTA to get to the airport.It's not unusual for riders to be late because of rail and bus delays or buses, in particular, that don't come at all. Plus the average time between buses, which is the only way to get beyond the limited area covered by the railway, is 30-45 minutes. The further out you need to go the worse the scheduling gets with times up to 50-60 minutes. That's scheduled time, not real-time during a rain storm or rush hour, and with bus drivers who barely get a break to relieve themselves or eat a meal. The lack of support from the city (which under the leadership of African American Mayor Shirley Franklin, whose tenure has had much better moments than this, was going to pony up $92 million--including up to $25 million in unidentified state funds--to "steal" the NASCAR Hall of Fame from Charlotte, North Carolina), and state speaks to the ingrained class structure and racial disparities in the city and state. Hotlanta may qualify as a Chocolate City, but Georgia is a predominantly white state. According to the Creative Loafing article those concerns determine where the money flows, and as a result the labor options for poor and working class African Americans and other marginal populations.

When it comes to spending money on transportation, most lawmakers and state employees heavily favor road construction instead. One possible reason for that can be linked to the influence of pro-road and pro-development groups like Georgians for Better Transportation. GBT President Mike Kenn and his organization enjoy exceptional access to members of the General Assembly, and to transportation planning agencies.

For instance, on Jan. 18, GBT hosted a Travis Tritt concert at the Fox Theatre. It was free for politicians and state employees; everyone else paid $10,000 a table. The concert was held at the same time that GBT lobbied behind-the-scenes to change the state's grading scale that determines which transportation projects get funded. GBT pushed for more consideration -- a jump from 10 percent to 70 percent -- to be given to "congestion mitigation," which most commonly calls for road-building.

Is this the same as the rural versus city conflict that hampers the State Assembly?

One of the biggest obstacles to fixing MARTA, Bullard and other transit advocates say, is the anti-inner-city sentiment saturating the General Assembly. Under the Gold Dome, any rural legislator seen as pro-MARTA historically has been attacked during a campaign as being anti-rural.Arguably, if there were a tornado at the level of a Katrina and requiring a similar level of evacuation, Atlanta would suffer a similar fate to New Orleans. We'd see major African American, Latina/o, and poor white displacement and only whites and Atlanta-area and suburban middle-class blacks, such as those annually portrayed in Black Enterprise's Best Cities for African Americans cover story and Henry Louis Gate's documentary on the state of blacks in the U.S., making it out and best able to rebuild. MARTA is continuing to have public hearings on the elimination of buslines, with some partial routes being subsummed by others--too bad if it's not the part of the route that takes you to your child's daycare. These forums seem a placating measure on the part of MARTA officials, but members of the black clergy are beginning to see this as a civil rights issue and Atlanta Jobs with Justice has already taken it on as a labor issue:

'If you're a representative or senator from South Georgia, you get re-elected by going back home and saying, 'Hey, I kicked Atlanta's butt while I was in the Legislature,''Rep. Jill Chambers, R-Atlanta, told CL last year. 'So we have to find some way to ... bring in the support of people from outside of metro Atlanta.'

Bullard believes the path to equality will be led by African-American grassroots groups and churches whose members think of access to transportation as a civil rights issue.I certainly hope that time is soon.

'The state will benefit if there is a healthy public transit service in the region so people can have alternatives and get out of their cars,' Bullard says. 'At some point and time, there needs to be a public uprising to say, 'It's time for this madness to stop.''

4 Comments:

ugg outlet

polo ralph lauren outlet

moncler outlet

ugg on sale

ugg boots

ray ban sunglasses outlet

nike trainers uk

ray ban sunglasses outlet

prada outlet store

hogan sito ufficiale

2017.11.1chenlixiang

hollister

vans outlet

chi hair

polo ralph lauren

nike air max

canada goose uk

cheap oakley sunglasses

nike blazer

adidas outlet

the north face

2017.11.14chenlixiang

zzzzz2018.5.17

jordans

jordan shoes

polo ralph lauren

moncler outlet

oakley glasses

golden goose sneakers

nike outlet

valentino

polo ralph lauren

tennessee titans jersey

Thank you for sharing an interesting and very useful article. And let me share an article about health here I believe this is useful. Thank you :)

Cara Menyembuhkan Selesma(Flu) dengan Cepat

Obat Penghancur Kista, Pengobatan Kista Tanpa Operasi

Obat Herbal untuk Limpa Bengkak

Cara Mengobati Konjungtivitis (radang mata) secara Alami

Obat Polip Telinga Alami Tanpa Operasi

Obat Nyeri Tumit Tradisional

Post a Comment

<< Home